This afternoon, I became profoundly saddened when I learned that Frederick Hammersley, one of my favorite painters, passed away on Sunday, at the age of 90.

An email newsletter from Charlotte Jackson Fine Art revealed the news. The subject line read Frederick Hammersley (1919-2009). Before I clicked to open the email, fearing the worst, I tried to trick myself into thinking that perhaps he would be having a new retrospective exhibition. To my disbelief, I was wrong.

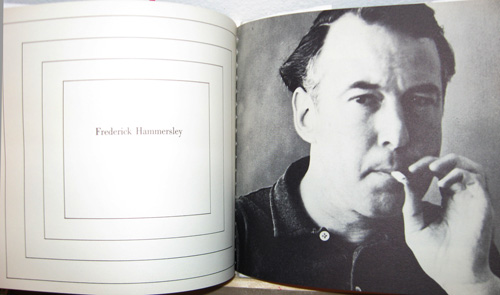

Frederick Hammersley, as pictured in the catalog of the 1959 Four Abstract Classicists exhibition

I would like to tell you why Frederick Hammersley’s work is so important to me. And I would like to explain my sadness for never writing him a letter, telling him how highly I think of his work, and how much I appreciate how he was able to pursue two very different styles of painting throughout his life (“geometries” and “organics”).

Why Hammersley matters

To me, there is no question that Hammersley is one of the greatest American painters of the 20th century. He’s up there with Barnett Newman and Mark Rothko. I’d love to see a Newman “zip” painting hung in the same room with one of Hammersley’s “geometries.”

However, the reason why Hammersley doesn’t have a larger following, in my opinion, is a simple question of geography.

Because they were based in Southern California, Hammersley, Karl Benjamin and other members of the Hard Edge abstraction group were thousands of miles away from New York, in a literal and figurative sense. While the West Coast Hard Edge painters were doing some truly astonishing, adventurous, highly original work, they didn’t fit the prevailing “discourse” of New York at the time. When the term “hard edge art” took shape in LA in 1959, pop art was right around the corner in New York; hard edge didn’t have a place in New York’s visual agenda.

Frederick Hammersley's In Two the Fray, #5 1978;

via Charlotte Jackson Fine Art - charlottejackson.com

And it is true that the Hard Edge Painters—the Four Abstract Classicists (Hammersley, Benjamin, John McLaughlin, and Lorser Feitselson)—were producing their own form of minimalism at the time. But again, they were ahead of their time—minimalist painting didn’t reach New York until the mid-1960s. These guys just didn’t “fit.”

“It was so brand-new,” Hammersley said, recounting how his paintings were received in 1959. “I assumed people couldn’t relate to it,” he says.

Despite not receiving the critical or curatorial attention he deserved, Hammersley carried on, painting away—way off the radar in Albuquerque—following his intuition, one painting at a time.

Yet, now, with hindsight—and thanks to Dave Hickey (who curated Site Santa Fe in 2001), Charlotte Jackson Fine Art (Hammersley’s gallery), Art Santa Fe (which will soon release a retrospective book of Hammersley’s works), and Elizabeth Armstrong (curator of the recent Birth of the Cool exhibition)—Hammersley’s profile certainly will increase.

Why Hammersley matters to me

I first encountered Hammersley’s work at Charlotte Jackson in July 2006, at the opening of his Hard Edge show, which blew my mind.

(Those IBM 14000 CORE mainframe computer drawings from the late 1960s!!!!!!!!!! I mean, renting time on a mainframe to make computer drawings, using punch cards? And one of the drawings is called Clairol? How utterly and insanely amazing is that! If only I could have been there to witness those being made!)

Anyway, three years ago, Hammersley’s show was exactly what I needed to see. I was in a point of transition, artistically, from painting neo-pop art to my own idea of minimal art. I was experiencing a lot of doubts about my decision, and I could tell I was leaving behind an audience in the process. I felt compelled to keep painting trippy pop paintings—because that’s what people said they liked—but I wanted to do something completely different.

After seeing Mr. Hammersley’s paintings in person, I felt like I had turned a corner—I had found a new artistic role model, if you will. He replaced Andy Warhol in my mind. It was “cool” to paint completely nonobjective work with just a couple of shapes in it. The show not only validated my own intuition, as a matter of fact, as I was leaving Charlotte Jackson, I literally turned around one last time and pumped my fist in the air. My reaction was that intense. I drove back to Phoenix beaming.

Following the Hard Edge show, I felt truly inspired to write Mr. Hammersley a letter. But somehow, I second-guessed the idea, as if it was too much of a stretch. I regret that decision.

But I am thankful to say that I was able to see the Birth of the Cool exhibition at the Blanton Museum of Art in Austin, Texas, two weeks before the touring show closed for good. While I swooned over Karl Benjamin’s loud-as-hell color combinations, Hammersley’s mid-1960s painting Come, really resonated with me. I can’t find an image of it online, so I must ask you to imagine four circles (as I remember, three are white, one black), arranged in the center of a cornflower blue rectangle, in a diamond configuration. The black circle is at the bottom. Yet, it’s not the circles, themselves, that do the talking, it’s the negative space between them. Genius.

We have lost a truly great painter—one of the greatest artists of our time. I know I am not alone in my sorrow. But I am comforted by the idea that so many artists and curators will be inspired by Hammersley’s work, and by his example, far into the future.

For reference:

- In Art in America: Seeing Hammersley whole: the octogenarian Frederick Hammersley was rediscovered by contemporary audiences at the SITE Santa Fe Biennial in 2001

- Charlotte Jackson Fine Art: An archive of articles, many of which relate to Hammersley

back when it was considered cool to smoke

An excellent post! Thank you for writing about such an important artist. He really should be linked to Barnett Newman and Mark Rothko among others, and given much more credit.

Have you read Dave Hickey’s recent article (about biennials) in Art in America, June/July issue? You might enjoy it.

Wishing you continued success!

Thanks for your comment, Melinda. I’ll be sure to check out Dave Hickey’s article in AiA. Perhaps I should renew my subscription! Anyway, hope you’ve had good feedback at the biennial.